Gene Healy

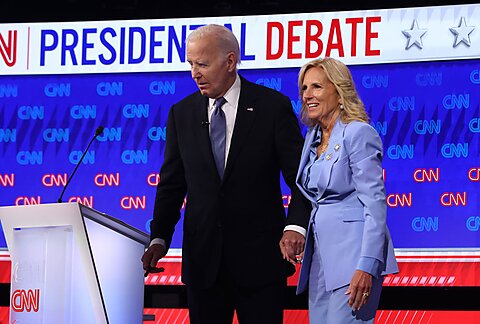

I’m just old enough to remember when people worried that a then-73-year-old Ronald Reagan was too befuddled to serve after he had a couple of “senior moments” in his first debate with Walter Mondale in 1984. If Reagan’s brief lapses were concerning, President Biden’s “senior 90 minutes”—his tragic, shambolic debate performance last Thursday—was a blaring alarm bell. Score one for the Cassandras of national decline.

“There’s a lot of people asking about the 25th Amendment,” House Speaker Mike Johnson said on Friday, “because this is an alarming situation.” And when people are asking about the 25th Amendment, it usually falls to me, as Cato’s resident 25th Amendment guy, to explain why it’s probably not going to happen. I did that on Friday’s Cato Daily Podcast, and I’ll do it again here: It’s probably not going to happen.

The 25th Amendment, ratified in 1967, was drafted in the wake of the Kennedy assassination. That grisly event highlighted the potential problem of presidential incapacity; what if, “instead of being mortally wounded, [JFK] had lingered for a long time between life and death, strong enough to survive but too weak to govern”?

The amendment’s drafters provided a potential remedy in Section 4. That provision allows the VP to take the keys away from the president when she and a majority of the Cabinet decide he is “unable to discharge the powers and duties of his office.” But when you look at how Section 4 works, you can appreciate why it’s unlikely to work as a means of getting Democrats out of their current predicament (much less the rest of the country out of ours).

Under Section 4, the vice president and a majority of Cabinet heads make the initial disability determination and notify Congress, at which point, “the Vice President shall immediately assume the powers and duties of the office as Acting President.” If the president challenges that determination, the question goes to Congress, and if two-thirds of both chambers ratify the switch, the vice president continues to serve as “Acting President.”

But as a practical matter, unless a supermajority of both houses affirms the decision, all triggering Section 4 does is put the president in a temporary timeout. As Sen. Birch Bayh (D‑IN), one of the amendment’s principal architects, explained: “[W]e were concerned about the politics of the palace coup,” so they deliberately set a higher bar than what’s required for removing the president via the impeachment process (which has also never happened).

Thus, even if Vice President Kamala Harris likes her odds and manages to coax along a Cabinet majority with enticing visions of “what can be, unburdened by what has been,” it’s all for naught unless she can muster the votes in Congress to make it stick.

Speaking of national decline, I’m also old enough to remember when people genuinely worried that Vice President Dan Quayle was too much of an airhead to be safely placed a “heartbeat away” from the presidency. There’s no way to put this politely, but Kamala Harris is almost as incoherent and rambling as President Biden, without the excuse of age. Would enough congressional Democrats favor a 25th Amendment solution that makes Harris the incumbent president and presumptive nominee? That’s not clear at this point, though recent polls that show her outperforming Biden may make that option more attractive.

But, given those polls, would enough congressional Republicans prove public-spirited enough to swap out a demonstrably feeble opponent just because the country might require a president who can be “dependably engaged” outside the hours of 10 a.m. to 4 p.m.? If not, Biden “resume[s] the powers and duties of his office.”

All plausible paths to a new Democratic nominee, whether Harris or someone else, involve President Biden stepping down voluntarily, as LBJ did in 1968. You’d like to think there was a point to Thursday’s cruel spectacle: that it was part of a plan toward convincing the president to withdraw. It’s possible to imagine a strategy session among the president’s handlers analogous to the following: “We all know that Dad really shouldn’t be driving anymore, but he’s not going to give up the keys unless he has an accident. So before we can have that difficult conversation, we’re going to have to let him crash the car. Let’s hope nobody gets hurt!” My guess is that there was no actual method to the madness, however. The Biden team stood him up hoping he’d muddle through. It didn’t work.

Looking beyond the 2024 horse race, this whole appalling episode brings three problems with the modern presidential system into stark relief. First, on both sides of the aisle, our primary-governed nomination process is a disaster, routinely elevating candidates who are unfit for office. When we pick people for the presidency, we’re not sending our best. Second, once presidents have assumed office, they’re far too hard to dislodge. In parliamentary regimes, “prime ministers may be removed at any time when Parliament is in session through a nonconfidence motion”; weak leaders can even be dumped by their own party without bringing down the government. In contrast, we Americans seem to be stuck with an elected pseudo-monarch, all but impossible to dethrone between four-year terms. Third, and most concerning, the modern president wields far more power than any one fallible human being ought to have.

All three are daunting problems, resistant to reform. Even if it were achievable, fixing the primary process wouldn’t help us right now, and lowering the bar to presidential removal would require a constitutional amendment. The “easiest” of the three, re-limiting presidential power, is still an extraordinarily heavy lift. But last Thursday’s debate is only the latest reminder of our urgent need to make the effort.