Jeffrey A. Singer

The New York Times today features an important article by reporter Jan Hoffman describing how what was initially perceived as an opioid‐related overdose crisis has morphed into a “polydrug” overdose crisis, with many nonmedical drug users combining stimulants with opioids, and often becoming addicted to more than one drug, making overdose reversal and substance use disorder treatment more challenging.

Hoffman reports that the last five years have seen methamphetamine‐related deaths triple and cocaine‐related deaths double. She reports that people addicted to opioids are increasingly using other substances as well, including psychostimulants like methamphetamine and cocaine, but also depressants and tranquilizers like Xanax.

This report helps bring attention to a fact I’ve been writing about for years: today’s nonmedical drug users are yesterday’s pain patients who became hooked on prescription opioids and now seek them in the black market. I mentioned in this 2019 blog post that, by 2017, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that 68 percent of opioid‐related overdose deaths were “polydrug,” i.e., toxicology reports revealed a mix of drugs in the overdose victims’ system. The New York City Department of Health reported in 2021 that almost half of all opioid‐related overdose deaths involved cocaine, and 41 percent involved alcohol.

Hoffman’s report brings to mind a 2018 University of Pittsburgh study I frequently cite, showing the overdose death rate has been on a steady exponential growth trend since at least 1979, with different drugs in fashion and predominating among overdose deaths at different times. It also reminds me of a 2017 study by Cicero and colleagues showing, “In 2005, only 8.7% of opioid initiators started with heroin, but this sharply increased to 33.3% (p<0.001) in 2015, with no evidence of stabilization.”

Hoffman writes:

A decade or so ago, Mexican drug lords figured out how to mass produce a synthetic “super meth.” It has provoked what some researchers are calling a second meth epidemic.

Hoffman devotes a significant portion of her piece to the second meth epidemic, providing powerful stories of some of its victims.

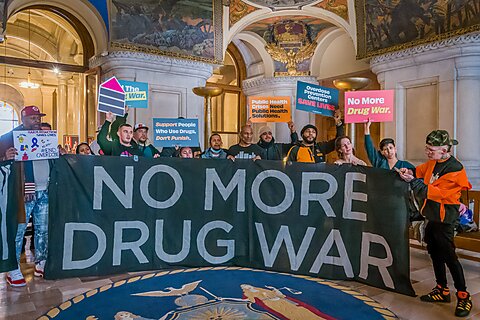

I wrote and told members of the House Judiciary Committee’s Subcommittee on Crime and Government Surveillance last March that the iron law of prohibition—“the harder the law enforcement, the harder the drug”—means we can expect more potent and dangerous forms of drugs to continue to arise.

In the case of meth, the Combat Methamphetamine Epidemic Act, which went into effect in 2006, drove the meth trade into the hands of the Mexican drug cartels, who quickly developed more efficient ways to make more potent meth while making patients waste billions of dollars on over‐the‐counter oral decongestants that are no better than placebo.

Alas, until policymakers come to terms with the fact that the polydrug overdose crisis and the “second meth epidemic” are the latest manifestations of drug prohibition, the cycle of harder enforcement yielding harder drugs and new drug “epidemics” will continue.