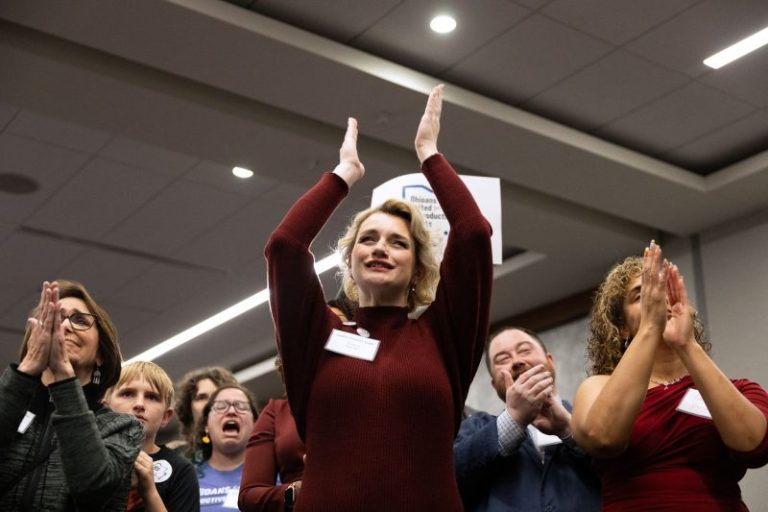

That Ohio residents voted Tuesday to encode access to abortion in their state constitution should not have come as much of a surprise. There had been six previous statewide initiatives centered on that question since the U.S. Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade, and each of the six had been successful, including in states redder than Ohio.

That it passed with 57 percent of the vote was also seemingly predicted by opponents of the measure itself, who tried to pass a new requirement this summer that any constitutional amendment would need 60 percent of support statewide to go into effect. Ohio’s Issue 1 landed right where opponents were apparently afraid it would.

Yet its passage triggered another, unexpected response. Not surprise, since that’s an inevitable reaction to political loss. Instead, it was the idea that somehow Ohio voters had been snookered, that the vote was not a function of the sincere belief that abortion should be accessible, but instead that voters had somehow been tricked.

This is a piece of a common, though obviously not universal, rhetorical line on the right: The left is acting not out of principle, but confusion. Republican losses aren’t because of opposition to the right’s policies, but because some nefarious force is changing people’s minds. It’s a neat trick that simultaneously absolves the right for pushing unpopular ideas and portrays their opponents as gullible sheep.

The most concise form of the propaganda argument in Ohio came from right-wing chatterbox Mark Levin. On social media, he wrote that “Republicans will continue to lose on the abortion issue because the Democrat[ic] Party and their surrogates spend [far] more on TV ads than the GOP spends on this issue, and the Democrats use those funds to lie about their true policy” — which he then proceeded to misrepresent. “The point,” he continued, “is people are voting on the propaganda they are being fed not the actual issue.”

Polling has repeatedly shown that most people in most states, including in red states, support abortion access. There is dispute about the conditions under which abortion should be acceptable, but there’s a consistent majority belief that it should be accessible under at least some conditions, which Issue 1 ensures without mandating that abortion be available whenever, wherever.

As the third Republican primary debate was underway Wednesday night, Fox News’s Sean Hannity interviewed former Arkansas governor Mike Huckabee about the party’s underperformance on Tuesday. Huckabee offered a broader version of Levin’s assertion.

“We recognize that an abortion has two victims: obviously, the unborn child, and the other victim is the woman who’s the birth mother, who probably got talked into abortion by a boyfriend, a friend, a mother, a grandmother, maybe a father,” Huckabee said.

This betrays a staggering misunderstanding of the issue. Women who support access to abortion — if I, yet another dude, might speak on their behalf — often center their support on having autonomy over their own bodies. This has been the subject of political and even philosophical arguments for decades. Yet it strikes Huckabee as more likely that women choosing to have abortions are doing so because they are being convinced to by someone else.

Again, this pattern appears elsewhere in right-wing rhetoric. It is taken as an article of faith, for example, that young people are being indoctrinated by liberal college professors to embrace left-wing policies and practices. When Elon Musk offered this up back in March, I looked at research on the subject that found no significant effect. (College professors, meanwhile, are probably startled to learn about their overwhelming influence on students who have to be cajoled to do the reading in the first place.) It seems more likely that the general liberalism of college students is a function of things like generally congregating in diverse urban centers and in shifts in political belief over time.

Young people are also a focus of another rampant claim about left-wing propaganda: TikTok. The video-sharing application, based in China, has become a boogeyman of the right (in particular, though not exclusively), including earning an extended conversation during Wednesday’s Republican primary debate.

“Let me say this: TikTok is not only spyware, it is polluting the minds of American young people all throughout this country,” former New Jersey governor Chris Christie argued. “And they’re doing it intentionally.”

This was in response to a question centered on the idea that TikTok is amplifying anti-Israel propaganda, a claim made both by congressional Republicans and, according to a CNN report, by the Biden administration. As journalist Ryan Broderick noted, this misunderstands the scale and fragmentation of TikTok, a platform that isn’t “based [on] mass appeal snowballing into global virality, but about identifying niches.”

Again, though, we see the same assertion: TikTok users and young people (overlapping groups) are credulous about the world, and we must shield them from this propaganda to ensure conformity with our worldview. That there were immediate responses on college campuses in the wake of Hamas’s attack in Israel would suggest there were existing belief systems about the region before this alleged TikTok nefariousness came into play. But it’s more comfortable to blame TikTok than it is to blame your own failures to persuade (which probably holds true here of the Biden administration as well).

Each of us thinks we are right about most things. Of course we do; if we didn’t, we would change our beliefs. When we run into people who disagree, then, we find it challenging. If that disagreement means we are blocked from something we want, it becomes frustrating.

One way to resolve this frustration is to try to convince the other person of your position, to find common ground or reach a compromise. Another way to do it is to go on Fox News, claim that the other person is brainwashed and bask in the agreement that results.

The former approach, it seems, is probably a better way to win elections.