Matthew Cavedon and Kayla Susalla

Earlier this month, the Oregon Supreme Court required the state to dismiss about 1,400 criminal cases because of a lack of defense counsel. The court held that misdemeanor cases must be dismissed after 60 days, and felony ones after 90 days, in the event counsel cannot be appointed. Some of the dropped cases include charges of aggravated theft and strangulation. Several other states, including Maine, Illinois, and New Hampshire, are also facing severe public defender shortages. Scarce resources call for an evaluation of the legitimacy of the charges being brought, especially for crimes that do not harm others.

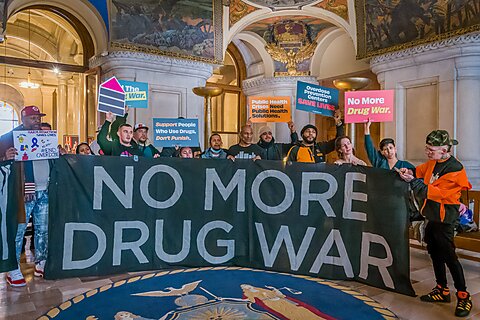

In Oregon’s case, the recriminalization of drug possession may be contributing to mounting caseloads. In 2021, Oregon passed a ballot measure that decriminalized the possession of small amounts of controlled substances. Individuals found with drugs faced no more than a $100 fine or a health assessment. The measure also created a recovery program funded in part by savings from reduced incarceration.

However, the timing of decriminalization made implementation challenging. COVID-19-era eviction prohibitions expired, displacing many people and making previously private drug consumption public. At the same time, Oregon’s healthcare systems were strained by the pandemic, limiting their ability to meet new treatment demands. The inability to keep up with rising healthcare demands, visible encampments, and the increase in overdose deaths due to the larger fentanyl wave led the Oregon legislature to recriminalize drugs in 2024.

The effort to decriminalize drugs was an attempt to emulate Portugal’s public health model. In 2001, Portugal decriminalized the possession of most drugs. Individuals found using drugs were fined modestly and referred to a panel of doctors, social workers, and addiction specialists. This approach was successful: HIV transmission from drug use, drug-related deaths, and incarceration rates fell significantly.

In contrast to Oregon’s response, Portugal’s approach was coupled with robust addiction treatment services and an increase in first responders referring people to such services. Other European cities, such as Zurich, Amsterdam, and Frankfurt, adopted similar decriminalization approaches, with strict enforcement against open consumption. A key component of these cities’ success was strong relationships between law enforcement and social services, supported by shared information systems. Frankfurt also led in establishing safe consumption sites. Leaders recognized a need for political and administrative consensus on drug policy for reform to work, and that new policies would take time to be successful.

In sum, decriminalization is not self-executing. It is most effective when paired with robust treatment capacity, coordinated public-order enforcement, and strong institutional cooperation.

As Oregon and other states become overburdened with heavy criminal caseloads, they should consider revisiting decriminalization. When resources are scarce, overcriminalization may undermine both justice and public safety.